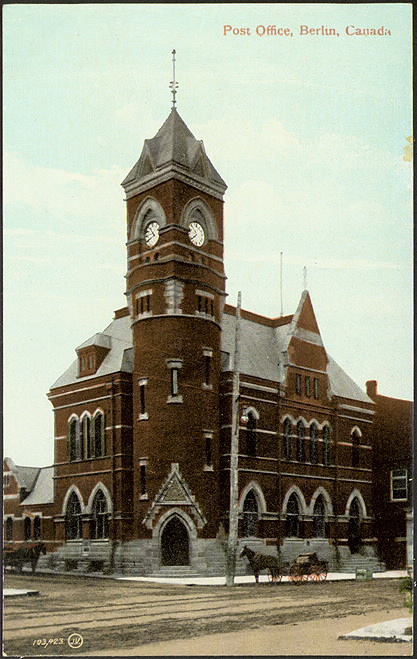

A ripple of excitement on the Bay of Berlin

The Berlin Daily Telegraph did a mini-exposé on William Kingsley, the man behind the injunction to stop the name change vote. A riffle through recruiting office files revealed he was a socialist slacker—this allowed a nebulous tie-in to the anti-name changer group with enemy aliens. Without proof of connection, the writer simply mentioned Von Papen, which allowed the reader to imagine the German spymaster’s hand in fronting the injunction’s legal fees. The opposition to the vote was dropped a few days before 19 May.

Preserving Berlin’s patriotism for all eternity

The 118th Battalion was undermanned to begin with and, in these fleeting days before training camp, not every soldier passed his final physical. A final push for soldiers was called for. Recruiters pled for four or five men from each factory to sign up, to keep the Battalion intact and prove the community’s good British spirit.

To bolster Berlin’s patriotic pride, city council allocated $270 ($5313—see note on conversion) to commission a moving picture of the Battalion. The Telegraph said it “could be displayed at future occasions and would also be shown to the leading cities of Canada in the next few years.”

“Berlin Battalion Warned”

On 15 May, The Toronto Star announced the latest antics in Berlin. General Hodgins (Adjutant-General for the Canadian Militia) and Colonel Shannon announced the 118th’s “rough tactics” were over and they would exhibit “better discipline.” The officers met with Mayor Hett and a dozen prominent citizens to investigate complaints about the Battalion—including “the midnight escapade.” The military men were shocked and indicated drastic measures would be taken to end the issue. They also visited the 118th’s officers “and after an hour with them, the men were lined up and a talk was given them which lasted only ten minutes but was sufficiently long enough for the most of them.”

Why won’t you talk to me?

(This week’s coverage of an issue concerning Mayor Hett is a good example of source bias. I’ve based this summary on The Berlin News-Record’s article, because it seemed less malicious and less like yellow journalism than The Telegraph’s reportage.)

As Colonel Lochead updated council on the Battalion’s activities, he referred to The Star’s article. He immediately went for the man, whom he believed to be present, who “endeavoured to bring discredit to the Battalion…This was his second offence and if he sent it, he should be man enough to admit it.”

Alderman Master wanted to suss out the man responsible for disgracing the city’s soldiers. Other councillors took the mayor to task for not telling his colleagues about the grievances or inviting them to the military meeting: “You notice it says ‘at which prominent men were present.’ We’re not prominent; that’s why we were not consulted about the matter!”

Hett said he was unaware an article would appear, and explained letters about the 118th’s behaviour were sent to Ottawa. “You may not know of the large number of complaints that reached me of fears of having church and other property destroyed…There have been rumours of what was going to happen before the Battalion left the city or in case the name of Berlin should not be changed. The public would be powerless.”

“Living under conditions of this kind, I felt there should be an investigation (so) I sent a communication to Ottawa…I felt that something had to be done to keep peace and harmony amongst our people. In view of speeches that have been delivered an in view of what has happened, I was perfectly justified in appealing to higher authorities.”

Aldermen Cleghorn and Hahn wanted to know who was at the meeting and why Hett didn’t discuss the issue at council. Hett sidestepped the first question and reminded his colleagues that he brought up issues at police commission and finance meetings, but the concerns fell on deaf ears. In view of everything that occurred, he felt “perfectly justified in not asking council.”

Hahn produced a notice Hett wanted to publish in the newspaper(s). It outlined assurances the Battalion would not interfere with the 19 May vote, and there would be no more disturbances in the city for the remainder of their stay. “Prominent citizens” convinced the mayor to withdraw the piece.

Hahn said, “It is plain that the mayor is behind the whole movement.” Master added, “The mayor knew if he asked us to back him up, we wouldn’t pay any attention to him.”

Alderman Gross tried to interject some level-headedness to the debate. The issue wasn’t a council matter, but one for the police commission. He also confirmed the mayor’s assertions that Berliners were afraid and wanted protection. Citizens who were concerned about the 118th’s antics also approached Gross for help. When he spoke to Col Lochead, the officer wanted firm proof that his men were at fault (which couldn’t be provided). When the alderman went to the police chief, he found “the police are also handicapped…I can’t blame the mayor for taking some action.”

Lochead defended his lack of action by saying official complaints had not been filed. He was also offended by such rumours about his men: “I have always invited intelligent criticism but all these reports…are nonsense.” He thought the Toronto article was a “direct insult to the officers of the Battalion,” and then claimed the Ottawa officers thought the 118th a prize bunch.

Cleghorn said the 118th was not responsible for the depredations, but “by the same men who were opposed to recruiting.” When he tried to attack Gross for not having any of his employee sign-up, he was corrected. More than a dozen of Gross’ employees volunteered. He then asked his would-be detractor, “Why isn’t your daughter a Red Cross nurse?

Cleghorn didn’t respond.

Alderman Rudell leapt in and continued to defend the 118th’s sullied reputation. The article and council discussion were disgraceful and more than he could comprehend. “We have General Hodgins’ statement that the Battalion is the best he has seen. We should show them our courtesy. The trouble has been that gossip has been taken for facts. It is certain that some of these people are glad to get rid of them.”

After more ballyhoo and bluster, council passed a resolution that admonished mayor Hett for not taking council into them into his confidence regarding rumours circulating about the 118th. Cleghorn, Dunke, Ferguson, Hahn, Hallman, Hessenauer, Master, Reid, and Rudell voted in favour; Gross and Huenergard were not in their chairs, and Gallagher, Schnarr, Schwartz, and Zettel did not vote.

Want a bit more information?

- About the Kitchener 1916 Project

- Bank of Canada’s Inflation Calculator was used to calculate modern price equivalents (2016)

The Recipe

There are a couple of different schools of thought when it comes to making Irish Stew. One is simply lamb (or mutton), potatoes, onions, and water; the other can include root vegetables (turnips, carrots), peas or barley. This recipe takes its cue from the meat-and-potatoes tradition, but can easily be adapted include more vegetables or barley. This is a really easy recipe that benefits from long, slow cooking and tastes better the next day.

Irish Stew (Miss Dora Mylius/ The Berlin Cook Book)

Take 2 pounds of neck or loin chops of mutton, peel and slice 2 pounds of potatoes and a pound of onions, first put into a stew pan a layer of potatoes, then chops and onions, and so on, till full, sprinkling salt and pepper on each layer, then pour in cold water or broth, cover the pan and stew over a very slow fire for an hour and a half, or until the meat be done. Before serving, add a few tablespoonsful of catsup.

Irish Stew (Adapted; Modern Equivalent)

Yield: 4-6 servings

| 750g | 750g | 1-½ lbs | Lamb neck or lamb chops (1 neck), cut into bite-sized pieces |

| 750g | 750g | 1-½ lbs | Potatoes, peeled and sliced |

| 375g | 375g | ¾ lb | Onions, sliced |

| Salt | |||

| Pepper | |||

| Beef or lamb broth or stock, as needed (approx. 1L) | |||

| 45ml | 45ml | 3 Tablespoons | Tomato ketchup |

Layer your stewpan as follows: potatoes, meat, onions; be sure to season each layer. Repeat the layering as necessary. Pour in cold stock, to cover the top most layer. Cover and cook over a low flame until the meat is tender—approximately 90 minutes.

When done, remove about a half-cup of broth and mix in the ketchup. Pour back into the pan. Balance flavours to taste.

Notes

- Add the bones into the pot along with the meat for a deeper flavour

- What I’d do differently:

- Dust the meat with seasoned flour and brown before layering.

- Caramelise the onions

- After layering the potatoes, meat and onions and pouring in the stock, bring the pot to a boil, then set in a 140C/275F for a couple of hours or until done.

- Instead of ketchup, use 1 Tablespoon tomato paste and 2 Tablespoons brown sauce (HP Sauce).

- For a thicker gravy, make a beurre manier

- Mix 3 Tablespoons each flour and butter. Mix in about a quarter cup of the pot liquor and then stir into the stew. Bring the pot back up to the boil for about five minutes.