Playing around with prohibition

Legislators added and refined clauses as they continued to debate the merits of Premier Hearst’s prohibition bill. Every municipality would have at least one licensed hotel (“standard hotels”), and boarding houses could bill themselves as such. For an annual licensing fee of $1 (just less than $20—see notes on conversion), these establishments could offer punters non-intoxicating drinks and beverages but also tobacco products. If the province’s druggists didn’t want to sell alcohol, wholesalers could handle it. There was talk about allowing brewers to sell directly to the public–to avoid the silliness of exporting beer to Quebec, only to have Ontario consumers import barley pops. Non-intoxicating drinks would continue to have a maximum alcohol content of 2.5 per cent.

Hydro issues burn bright

Over the past couple of weeks, the Hydro Electric Commission campaigned to bring electricity to farmhouses and outbuildings. Some farms in the Berlin area already “(enjoyed) the advantages of electricity.” It was hoped this modernisation would help quell the exodus of young people from rural Ontario.

Meanwhile, the McGarry Bill sparked charged debates. If passed, the Hydro Commission’s surpluses would transfer to provincial coffers, and a comptroller would oversee expenditures. Many were suspicious. They saw it as a step towards privatisation because municipalities would be stripped of their voice. Sir Adam Beck‘s position as chairman seemed to teeter, since this new comptroller could assume some or all of Beck’s various responsibilities (as and when required). After much discussion over the comptroller’s “joker clause” its elastic role would be curtailed.

Good-bye, Berlin-to-Toronto high-speed rail

Even though Hearst said he had no plans to weaken Hydro, the radial lines subsidy was a no-go. The premier believed “they were all agreed in the present situation that it was not the time to embark on capital expenditure in enterprises of this kind and that they were all desirous of conserving their strength, financial and otherwise in the way of winning the war.” Without these subsidies, Beck’s plans to connect Ontario’s communities—while strengthening Hydro’s position—was essentially dead.

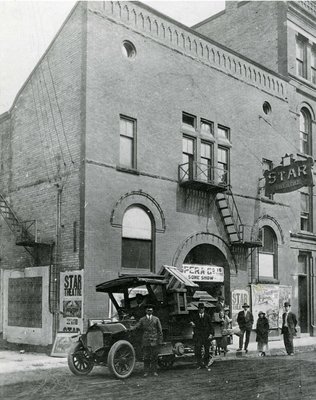

Another meeting of the people

Berlin’s city fathers invited everyone—including women—to the Star Theatre to hear about their (mis)adventures at Queen’s Park.

The evening was filled with the expected bullyboy bravado from the name change contingent. Alderman Master reviewed what happened at the Queen’s Park hearing and vowed to not let the matter drop until Premier Hearst and the Private Bills Committee gave his side a fair hearing. American-born shirt manufacturer SJ Williams’ hour-long speech was “charged with explosive facts” about his almost year-long campaign to rid the good city of its not-so-good name. Colonel Lochead rat-a-tat-tatted a rhythm line linking counter-petition signers to German sympathisers. Alderman Hahn questioned why Berliners should keep politicians who don’t work to change the city’s name.

Anyone who either wanted to keep Berlin’s name or wanted the people to have a say were targets of mud and mire. “A serious case” kept Mayor Hett away, which afforded Alderman Cleghorn the opportunity to exercise his special brand of aplomb; Hett was also targeted for not publicly declaring his allegiance (and, presumably, wanting to have public input). MP CH Mills allowed counter-petitioners too much weight in the issue and didn’t apply the right pressure on his Conservative seatmates. Alderman Gross was attacked for opposing this patriotic act, and was the target of a thinly veiled accusation of perverting military recruitment—he supposedly bribed his son with a new car, to not sign up. None of the three men attended their flaying.

Attendees passed a resolution that protested the Committee’s actions. According to The Berlin Daily Telegraph, it was a “strong indication that the loyal citizens of Berlin will not allow their patriotism, to the cause for which Britain and her allies are fighting, to be trifled with by the legislature, the Private Bills Committee the local representatives or set of politicians catering to the German vote of the community.”

Fireworks at council

The councillors’ cantankerous caterwauling continued a few days later, at the next council meeting, this time in front of a smaller audience of approximately 20 name changers. Media reports declared the words bitter, accusatory and filled with insinuation.

Hett was, again, pressed to declare his position on changing Berlin’s name. And, again, he refused: “I do not consider it in the public interest of the city that I should declare myself on this question.” Council and the gallery howled with laughter.

Needless to say, this cued Cleghorn’s standard attacks on the mayor and those whose patriotism didn’t extend to changing the city’s name, “It was the duty of all loyal citizens of this city to get rid of the name as soon as possible.” Machismo broke out when Hahn asked the mayor if he was “a man or a mouse” (to which Hett replied “I am just as much of a man as you!”).

Gross prefaced his remarks “by intimating that the promoters of the name change movement are on their way to a place reputed to be warm and uncomfortable.” He then questioned the Britishness of the Britisher delegation for dining at German hotel to eat German food when in Toronto.

Alderman Reid brought up a two-year-old incident when the Board of Trade opened a meeting with Die Wacht am Rhein, and wondered how many of these patriotic aldermen raised the Union Jack at home. When Representative Hessenauer retorted that he was as British as Reid, Reid challenged him to change his surname.

Council passed a resolution to take the name change back to the Legislature, 11:4.

Another audience at the Legislature

Canadian Press’s wire service announced the Legislature would jam through an amendment to allow council to change the city’s name, as long as there was a public vote. A delegation made up of city council, representatives from the 118th Battalion and other interested citizens, met with Attorney General IB Lucas (who also chaired the Private Bills Committee). The Berliners “demanded, and in an aggressive manner, too, that the name of the city be changed.”

At the meeting, delegates reycled the same arguments once and again.

The city’s solicitor, Mr Sims argued for the renaming as “the seed of pro-Germanism exists and it only needed to be developed” and voting on a name change may simply provide the opportunity for that seed to root and flourish. If citizens voted on the matter, the result would be “injudicious and unwarranted.” With these dire consequences in mind, he declared an order in council or an act of the legislature would be needed to change the name.

The 118th’s Captain Walters claimed the Committee’s action hurt recruiting efforts and “Some of the Germans up there actually insult our soldiers on the streets.” (Spurious, at best: The insults probably had less to do with the name change, than the Battalion’s recent escapades.) Lucas responded, “Well, cramming this name down their throats won’t make them any more loyal will it?” True to form, the military man deflected the Attorney General’s logic.

Then Lucas played a card straight out of the (absent) counter-petitioners’ hand: “Suddenly Hon IB Lucas saw a solution and said he would allow the municipality take on a vote on changing the name, and if favourable then the name could be changed by the Railway Board or Chief Justice.”

What could the name change delegation do? They were antipathetic to the electorate’s voice or opinions, and would have rather have imposed their will on citizens. If they declined, this battle and the entire war would be lost. They agreed to Lucas’ recommendation, but one could only imagine the train ride home.

Want a bit more information?

- About the Kitchener 1916 Project

- Bank of Canada’s Inflation Calculator was used to calculate modern price equivalents (2016)

The Recipe

The 1906 Berlin Cookbook seemed to favour cabbage. Not terribly surprising, as one would assume to find variants of sauerkraut, coleslaw and salad (as is today’s recipe), stuffed cabbage, and sours and pickles. But leaves were also key players in clam chowder, patties, sauces and salad dressings, and vegetable stuffings.

Mrs A Phelan’s recipe for cabbage salad was not what I expected for an early 20th Century recipe. I’d become accustomed to sparsely spiced and timidly flavoured foods, so when I saw mustard, ginger, cloves, and cayenne, I decided the good Mrs Phelan was a bit of a wild child by comparison. The result is a sharp and spicy salad that pairs well with pork ribs and sausages. Bravo. We all need a bit of Mrs Phelan in our cookery.

Cabbage Salad by Mrs A Phelan. (1906 Berlin Cookbook)

1 gallon cabbage finely chopped, 1 pint onions. 3 tablespoons fine mustard, 1 tablespoon ginger, 1 tablespoon cloves, 1 tablespoon cayenne pepper, gallon of vinegar. Mix well and boil 20 minutes.

Cabbage Salad (Adapted; Modern Equivalent)

Yield: 8 servings

| 100g | 125ml | ½ Cup | Sugar |

| 20ml | 20ml | 1-½ Tablespoons | Mustard powder |

| 6ml | 6ml | 1-½ Teapsoons | Salt |

| 6ml | 6ml | 1-¼ Teaspoons | Ginger powder |

| 6ml | 6ml | 1-¼ Teaspoons | Ground Cloves |

| 6ml | 6ml | 1-¼ Teaspoons | Cayenne pepper |

| 750ml | 750ml | 3 Cups | Apple cider vinegar |

| 550g | 2L | 8 Cups | Shredded cabbage |

| 100g | 250ml | 1 Cup | Slivered onions |

Dissolve the sugar and spices in the vinegar and bring to a boil. Add the cabbage and onions. Let boil for 20 minutes. Serve warm or cold.

Notes

- I decreased the amount of vinegar called because I felt it was too much for the amount of cabbage. I kept the spicing amount roughly scaled to what was called for in the original recipes. If you find it too spicy, well simply decrease the amounts of spices used.