The long, slow vote to a new name

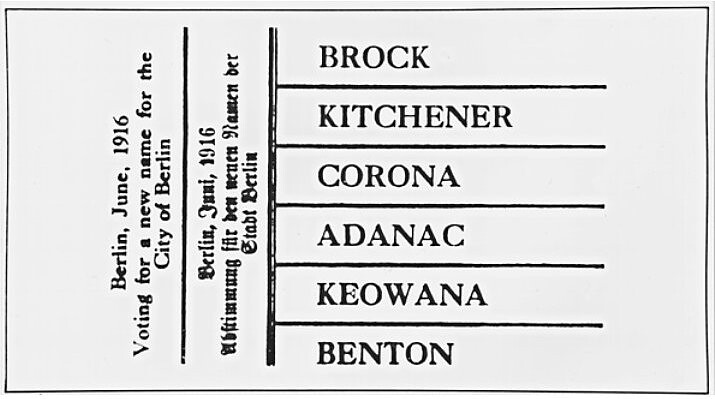

It seems any worries about a mad stampede of passionate voters to the referendum poll were for nought. To avoid a one-day rush, organisers decided the polling station (yes, singular) would be open from 9 am to 9 pm for four days (from 24-28 June (but not on Sunday the 25th)). This way, the nearly 5000 eligible voters could choose a new name for Berlin, Ontario with little chance of fuss or muss.

Interested electors dribbled in. The only burst of activity happened early when some the 118th Battalion, who were on weekend leave from London, Ontario’s camp, marked their “x” against their name of choice. According to The Berlin News-Record, “Had it not been for the soldiers home for the weekend casting their ballots for a new name, Saturday’s voting figures [130] would have been smaller still.”

A new name is chosen

At about 9:45 pm on 28 June, Berlin’s city clerk announced the results to a waiting crowd at city hall. Voters selected “Kitchener.” Although it was a horserace for the two most popular names (Kitchener beat Brock by 11 votes) the remaining four names had little support.

How many people cast a ballot isn’t clear because The News-Record and The Berlin Daily Telegraph reported different numbers. The News-Record reported 892 votes, while The Daily Telegraph reported a range of 800-825. Both papers agreed the returning officers counted 729 unspoilt slips.

Some ballot spoilers made their feelings known. If they didn’t want to change the name, they wrote “Berlin” on their slip. If they wanted to amalgamate with the neighbouring town, they wrote “Waterloo.” Others crossed out every name on the ballot (their reasons are anyone’s guess). The Daily Telegraph reported a campaign to attract 200-300 people to spoil their ballots was afoot.

The Results

| Name (as per ballot order) | Number of Votes | Percentage of unspoilt votes |

| Brock | 335 | 45.95 |

| Kitchener | 346 | 47.46 |

| Corona | 7 | 00.96 |

| Adanac | 23 | 03.16 |

| Keowana | 3 | 00.41 |

| Benton | 15 | 02.06 |

| Total | 729 | 100 |

Reaction to the results seemed rather staid, unlike the bylaw change referendum a month earlier. There was no parade of cars carrying hooting and hollering partiers or a military band root-a-toot-tooting before thousands of onlookers. There were no triumphant speeches. The King didn’t even receive a telegram. There was only relief that the name-change campaign and all its related issues would soon end.

Now, what?

City council was expected to pass a bylaw to change the city’s name from Berlin to Kitchener next Monday. Afterwards, it would be forwarded to the Lieutenant-Governor-in-Council for ratification. Assuming all went well, his proclamation would set the official change-over date.

In case anyone had forgotten about the naming contest, it was suggested that those who nominated Kitchener, Brock and Adanac would be in line for the prize money.

What the pundits said

Only a small fraction of the eligible 4897 ratepayers participated in the referendum—somewhere between 16-18 per cent of eligible voters (depending on which set of turnout numbers to believe) went to city hall. The counted votes were less than a quarter of the 3057 that were cast to determine whether or not the city should get a new name. The number of counted votes was also less than half of the number who voted to shed the old German name.

The day before the count, The Daily Telegraph reported the usual turnout for a bylaw vote was 800-900. The day after the clerk announced the results, the paper said there were 468 votes cast for a bylaw vote that occurred three years earlier. The writer also reminded readers of the number of votes that put Alderman Gross on council that year—he received 986 votes, “the highest on the list.” The writer also mentioned fewer than 60 electors attended nominations for the various municipal bodies.

Meanwhile, The News-Record declared the turnout for the name selection was “the lowest vote ever polled in the city,” and “the outstanding feature of the recent voting upon the name changing question, which closed at 9 pm last evening at city hall was the absolute indifference displayed by the ratepayers.”

Newspapers pointed out two reasons for the low turnout:

- There was no organised effort to get out the vote. For May referendum, weeks were spent arguing both sides of the issue and rallying the troops; more than 3000 people voted. For this vote the ballot’s shortlist was only decided one week earlier. While not rallies, editors included persuasive pieces in their pages: “word on the street” -type snippets touting Brock and Kitchener, as well as gloried obituaries and discussion about the late Earl Kitchener. No groups were organised to rally support for any particular name or even to ensure people got out to cast a vote.

- The front-running names, Brock and Kitchener, were signalled at the selection meeting and repeated in the newspaper pages. One writer argued that as neither was particularly objectionable to electors, they didn’t appear at the voting booth.

Another possible reason for the low voter number, which wasn’t mentioned, was the physical inconvenience of voting. Instead of setting up polling stations in each ward (as what happened in May and I believe in the January municipal elections), people could only vote at city hall. While some may have argued that Saturday should have been the busiest day (because it was only a half-day at the factories (leaving the rest of the day to vote)), it seemed the electorate had other things to do with their time.

Editorials

As expected, the local English-language newspapers approached the results with different lenses. The Daily Telegraph suggested “Brock” did well because of “its brevity and euphonious sound, and many who voted for it did so because it commenced with the letter ‘B,’ which would have saved considerable expense in adopting new trademarks, etc.”

“Kitchener,” however, honoured the late British secretary of war, who “stood for efficiency which has been the secret of the success of the industrial life of this city.” The name was “British and stands for loyalty and devotion to the British Empire and her institutions, which is the direct opposite of the name “Berlin” and that for which it stands.”

The News-Record, a proponent of amalgamating with Waterloo, included sections of a letter from Thomas Adams, Ottawa’s municipal planning advisor and “one of the foremost town planning experts of England” in its editorial. He favoured “Waterloo” as the joined city’s name, and observed that choosing Kitchener would be unfortunate because “Lord Kitchener’s name is imperial, rather than local in its significance.”

The article pegged low turnout to the fact that “Waterloo” wasn’t an option, and many didn’t want to vote down a popular hero, so 80 per cent of the electorate simply didn’t vote. The writer argued, since the best scenario would be to satisfy the majority, amalgamation should happen, and the joined city should take on Waterloo’s name.

Want a bit more information?

- About the Kitchener 1916 Project

- Click here to read a summary of shortlisting Berlin’s possible names

The Recipe

I found this recipe as part of a set of sour milk recipes extolling grandmother’s thrifty ways. It seems, regardless of generation, the current generation thinks those before were more resourceful with food.

Like the previous cream cake muffins, this recipe is for gems—very much like muffins or cupcakes, but smaller and shallower. You don’t need a gem pan (or as I used, my whoopee pie pan) to make these—a standard muffin tin will do.

Graham Gems (Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 1 June 1916)

To one egg, well beaten, add one-third cupful sugar, one cupful sour milk, one level teaspoonful soda, one tablespoonful butter, and one heaping cupful graham flour. Bake in a quick oven

Graham Gems (Adapted; Modern Equivalent)

Serves: 6-10

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Egg |

| 110ml | 87g | 1/3 Cup + 2 Tablespoons | Sugar |

| 270ml | 270ml | 1 cup + 4 Teaspoons | Buttermilk |

| 4ml | 4g | 1 scant teaspoon | Bicarbonate of soda/baking soda |

| 17ml | 16g | 1 Tablespoon + ½ Teaspoon | Butter, melted |

| 280ml | 175ml | 1 Cup + 2 Tablespoons | Graham flour |

Preheat oven to 190C/375F. Insert paper liners in a muffin pan.

Beat together the egg, milk and melted butter

Whisk together the bicarb and graham flour

Mix the wet into the dry until just combined,

Fill the prepared muffin tins and bake until done (see notes)

Notes

- I scaled this recipe to a large egg (chances are the eggs used 100 years ago were equal to our medium eggs).

- I don’t have a gem pan, but to try to be authentic, I used my whoopee pie pans and baked them for about 15 minutes. If you were to do these in a muffin tin, I would think it would take longer—a total of 20-25 minutes, I think—but keep an eye on them.

- For more information on Canadian egg sizing, please visit the Egg Farmers of Canada’s website